When Neanderthals Dreamed in Color: Rethinking the Origins of Art

We weren't the first to dream in pictures; our story starts with hands pressed to stone.

By Jim Walker, December 2025

Introduction

When I read the latest dating papers on cave art, I didn't picture lab coats. I pictured a person standing in the dark with a handful of red pigment, taking a breath, and pressing their hand to cold stone. The record is messy and detailed: red ochre handprints, hunting scenes, and deliberate cross-hatched “hashtags,” all laid down tens of thousands of years ago[1].

For a long time, we told ourselves a simple story: that we were the first to dream in pictures. That symbolism belonged only to Homo sapiens. That art began with us. The latest discoveries put that old belief to rest.

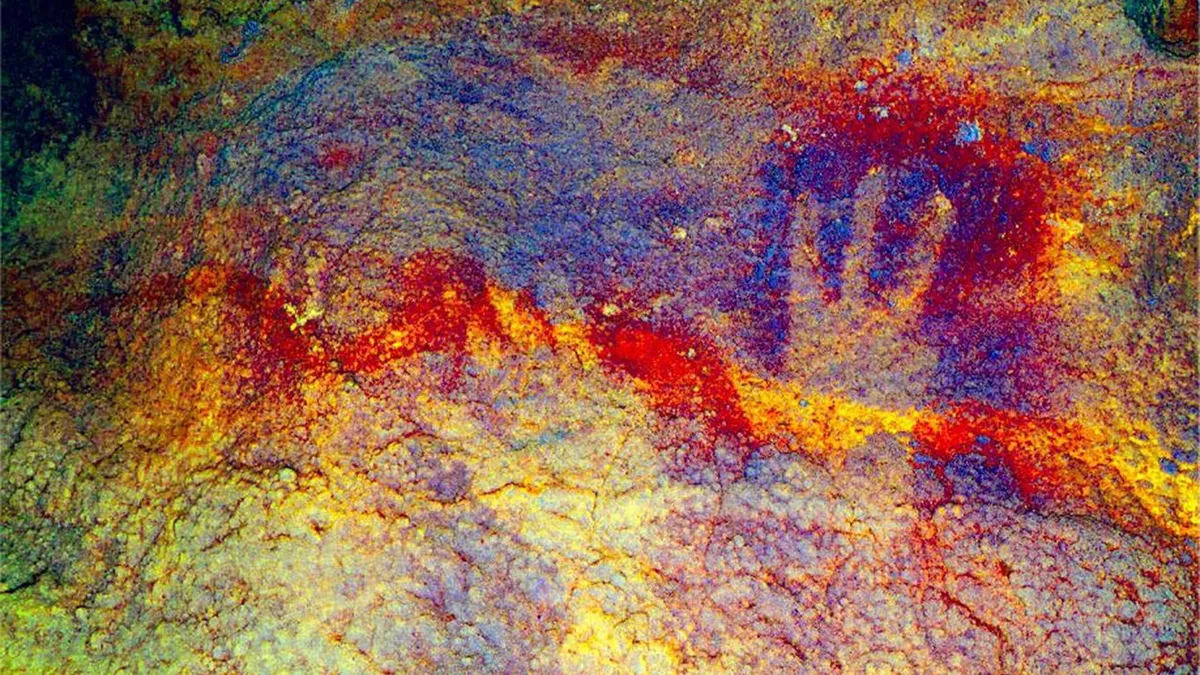

- Neanderthal handprints on cave walls in Europe [4].

- A hunting scene in Indonesia painted 51,000+ years ago[1].

- Age-old tiny etched stones in South Africa that look like deliberate symbols, including the oldest known drawing from the Blombos Cave[5].

Follow the trail far enough, and a different picture emerges: multiple kinds of humans, on different continents, thinking in images long before we ever knew they were there.

The Problem

Once researchers applied Uranium–Thorium dating and high-resolution laser-ablation scans to the calcite crusts over cave art, the timelines started to fall apart. Each new measurement pushed the art, and the people behind them, further back in time[2].

"The beginning of art keeps sliding deeper into the past and farther out across the globe."

The pattern starts to feel personal: Neanderthals painting, hunters in Sulawesi pinning stories to rock, early humans in Africa carving careful cross-hatched marks as they work through ideas. Different branches of the human family, scattered across continents, all answering the same impulse to fix their world in place before it slipped away.

Why It Matters

Those old red handprints were not rough first attempts. They appear as surviving pages of a very long sketchbook. Seen together, they read like records left with purpose. Art did not begin with a single “artist” in a single European cave. It looks like a shared language that many kinds of humans were already speaking.

When you draw, paint, design, or even doodle in the margins, you’re joining a story that started long before our species had a name.

That is the part that stays with me. Across at least 50,000 years of experiments in pigment and line, a group of strangers we will never meet keep doing something recognizably human: leaving a trace and hoping someone will see it. Each new date becomes another interview in an ongoing investigation, and across all that distance we are still answering those first painted hands on the wall.

The Paleoanthropological Record of Early Art

Rethinking the "Human Revolution" model

For much of the 20th century, paleoanthropology leaned on what was called the "Human Revolution" model. This hypothesis held that while anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago, "behaviorally modern" humans (those capable of abstract thought, symbolism, and art) only emerged about 40,000–50,000 years ago. This change was often linked to the migration of Homo sapiens into Europe and the sudden appearance of spectacular cave art in sites like Chauvet[10], Lascaux, and Altamira.

Using that as evidence, it appeared that art only belonged to Homo sapiens—a bright line that supposedly split ‘us’ from ‘them’ (Neanderthals included). Europe’s famous cave walls were treated as the proof.

Over the last decade, however, new dating technologies have systematically dismantled this view. Radiometric advances, especially Uranium-Thorium dating, have pushed the timeline of art back even further. We now know that symbolic expression predates the European Upper Paleolithic and is not restricted to our species. The new evidence supports a gradual, cumulative evolution in how we think in pictures, emerging across vast distances from southern Africa to the islands of Southeast Asia.

New Tools: Uranium-Thorium Dating

Understanding why our art history is changing requires a look at how we measure time. The re-dating of key sites like Leang Karampuang in Indonesia and the Spanish caves associated with Neanderthals relies not on traditional radiocarbon (C-14) dating, but on Uranium-Thorium (U-Th) series dating [2].

Why Radiocarbon Falls Short

Radiocarbon dating has long been the workhorse of archaeology, but it struggles with ancient cave art for two core reasons:

- Material limits: C-14 dating requires organic material (charcoal, bone, plant fibers). Many cave paintings, especially red ochre hand stencils and geometric signs, were made with inorganic pigments (iron oxide) that contain no carbon. They simply cannot be dated with C-14.

- The ~50,000-year "radiocarbon barrier": Because the half-life of C-14 is only 5,730 years—meaning half the original carbon-14 decays every 5,730 years (then 1/4 after 11,460 years, 1/8 after 17,190)—after about 50,000 years so little radiocarbon is left that it becomes very hard to measure. Beyond that point, the remaining signal is usually too weak and too easily swamped by contamination to date the sample reliably.

The U-Th Solution

U-Th dating sidesteps this problem by measuring the radioactive decay of uranium-238 into thorium-230 in thin calcite crusts. Uranium is water-soluble; thorium is not. When water percolates through limestone, it picks up uranium and deposits it in new calcite layers on cave walls. At the moment that calcite forms, it contains uranium but essentially no thorium. As uranium decays over time, thorium accumulates at a known rate, so the uranium/thorium ratio becomes a clock.

If a painting is covered by a film of calcite, dating that crust gives a minimum age for the art beneath it. The artwork must be older than the calcite that formed over it. The magic! This means even inorganic ochre paintings can be indirectly dated by the mineral layers sitting on top of them.

Laser-Ablation: Dating at Micron Scale

A newer advance, used in the Indonesian work, is laser-ablation U-Th imaging. Instead of drilling a single bulk sample, scientists vaporize ultra-thin layers of calcite with a laser and map uranium and thorium through the crust, micron by micron. This allows them to target the micro-layer touching the pigment itself and produce much tighter minimum ages. In several cases, this approach has revealed that art is thousands of years older than earlier estimates suggested[1].

The Sulawesi Discovery: The Oldest Narrative Art

The Indonesian island of Sulawesi sits in "Wallacea," a deep-water zone between Asia and Australia. Reaching it more than 50,000 years ago, its first human inhabitants were almost certainly people already comfortable moving across open water. In the limestone karst of Maros-Pangkep, archaeologists have found the world’s oldest known narrative cave art.

The newly dated scene sits in a limestone chamber at Leang Karampuang in the Maros-Pangkep karst of South Sulawesi. Using laser-ablation U-Th sampling through the thin calcite crust over the paint, the team pinned down a minimum age of 51,200 years. In their paper and in later anthropology and arts coverage, the pig-and-therianthrope mural is now treated as the oldest known example of pictorial storytelling, not just a single animal painted on a wall[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18].

Leang Karampuang: How the Story Came to Light

In 2024, a team led by Adhi Agus Oktaviana, Maxime Aubert, and Adam Brumm published findings in Nature showing that the main panel in Leang Karampuang carries a minimum age of 51,200 years[1]. Their measurements push the record for narrative cave art past the 50,000-year mark and place this small limestone chamber at the front of our current timeline for storytelling in paint.

The scene:

- A large wild pig, identified as a Sulawesi warty pig (Sus celebensis), dominates the panel. It is painted in dark red ochre and measures close to a meter across.

- Around the pig are three smaller, human-like figures with animal features (therianthropes) holding what appear to be ropes or spears. Their poses clearly suggest action: a hunt in progress rather than an isolated animal.

This is not just a picture of a pig. It is a story fixed in stone, with several beings caught in the same moment and the same scene.

The science behind the new date:

Using laser-ablation U-Th imaging, the researchers dated calcite crusts overlying the pigment. The oldest layer returned an age of 51.2 thousand years. That makes the Leang Karampuang panel around 6,000 years older than the previous record for figurative art, a warty pig painting at Leang Tedongnge (at least 45,500 years old)[9], also on Sulawesi.

Why narrative matters:

A figurative painting depicts recognizable subjects; a narrative painting arranges them in a way that conveys an event. In the Leang Karampuang mural, human-like hunters and a pig are composed into a coherent visual story. That means the artist had to hold a whole event in their head and freeze it as a single image.

The therianthropes take it even further. These human-animal hybrids do not exist in the everyday world. Imagining and painting beings that are part-human, part-animal points toward mythology, spiritual belief, or at least a rich imagination. The artists were not just recording what they saw. They were painting what they could imagine.

A Broader Cultural Context

The presence of such sophisticated art in Wallacea reshapes our assumptions about early human migrations. Homo sapiens likely reached Australia by ~65,000 years ago, passing through Indonesia[19]. The quality and complexity of the Sulawesi art suggests that these populations carried a developed symbolic culture with them, rather than inventing it only after arriving in Europe.

Taken together with other Southeast Asian finds, the Sulawesi record points toward a widespread origin of art: multiple human groups in different parts of the world experimenting with images, symbols, and stories over tens of thousands of years.

The Iberian Evidence: Neanderthals as Artists

While Sulawesi illuminates the early art of our own species, discoveries in Spain have pushed the story beyond Homo sapiens entirely. In 2018, a study by Hoffmann and colleagues, published in Science, provided strong evidence that Neanderthals were painting caves more than 64,000 years ago[3].

Three Caves, One Big Surprise

The U-Th dating focused on three key sites in Spain, each with red ochre markings:

- La Pasiega (Cantabria): features a complex red geometric "ladder" or scalariform symbol composed of vertical and horizontal bars. The carbonate crust over it yielded a minimum age of about 64,800 years.

- Maltravieso (Extremadura): contains a red hand stencil created by blowing pigment around a hand pressed against the wall. The overlying calcite dates the stencil to at least 66,700 years ago.

- Ardales (Andalucía): preserves stalagmites and other formations intentionally daubed with red pigment, with U-Th dates around 65,500 years.

All three caves predate the earliest evidence for modern humans in Europe by over 20,000 years. That means these marks, from hand stencils to geometric symbols and painted stalagmites, must have been made by Neanderthals.

What This Tells Us About Neanderthal Minds

Thinking in pictures: The Iberian paintings aren't tools. They do not sharpen tools or butcher meat. They are symbols.

A red, ladder-shaped geometric sign (a so-called scalariform motif) at La Pasiega is an arbitrary design that likely encoded meaning understood by its makers. A hand stencil at Maltravieso is a personal calling card: it says "I was here." In Ardales, pigment was carried deep into the cave and applied to natural features in a selective way, suggesting ritual or aesthetic intent.

Taken together, these acts show that Neanderthals were thinking at a high level. They were capable of abstraction, symbolism, planning, and shared traditions. They were, in many ways, thinking like us.

Planning and cooperation: Making cave art is a serious endeavor.

- Artists needed access to pigment sources, and the know-how to grind and mix them.

- They had to carry these materials into deep, dark cave chambers, using torches for light.

- They selected particular surfaces and formations, not just random rock faces.

This is not trial-and-error behavior. It reflects foresight, coordination, and a sense that particular places and images mattered.

A shared inheritance: If both Neanderthals and early modern humans created art, then the roots of symbolic behavior likely stretch back to a common ancestor, often identified as Homo heidelbergensis (around half a million years ago)[20].

In that light, art does not appear to have been a sudden "light switch" that flips on with Homo sapiens in Europe. It looks more like a light dimmer knob, turning slowly but steadily brighter over hundreds of thousands of years across multiple branches of the human family tree.

Blombos Cave: Early Experiments in Marks and Color

While big cave murals get most of the attention, the roots of artistic behavior often show up in smaller things you can hold in your hand. On the southern coast of South Africa, Blombos Cave has turned up some of the oldest known evidence for abstract marking, careful pigment processing, and deliberate drawing. These are not showpieces for a gallery. They are samples of people thinking with lines and color.

The 73,000-Year-Old "Hashtag" Drawing

In 2018, researchers announced the discovery of a silcrete flake (known as L13) bearing a cross-hatched pattern in red ochre. The design looks a lot like the modern hashtag. It comes from archaeological layers dated to about 73,000 years ago, making it the oldest known drawing made by a human hand[5].

What it looks like:

- Six parallel red lines are crossed by three shorter, slightly curved lines, forming a deliberate, graphic pattern.

- Microscopic analysis and experiments show the lines were drawn with an ochre "crayon," not carved with a sharp tool.

- The strokes stop abruptly at the edges of the flake, which suggests the drawing was originally part of a larger design on a bigger piece of stone that later broke apart.

This is not just random scribbling. The regularity of the lines, their spacing, and their repetition in other engraved pieces from Blombos strongly suggest a shared symbolic design.

The Blombos Workshops: A 100,000-Year-Old Paint Studio

Even older than the drawing are the pigment workshops at Blombos. In sediments around 100,000 years old, excavations uncovered an ochre-processing "studio" [7] with abalone shells used as containers.

- The shells held a red, ochre-rich mixture combined with bone, charcoal, and possibly fats, an early form of paint or protective compound.

- Grindstones, hammerstones, and ochre chunks were found alongside the shells, forming a complete toolkit for pigment production.

- The mixture appears to have been stored for later use, showing planning and an understanding of recipes.

This is chemistry and design in ancient times. The people at Blombos were sourcing materials, mixing them in specific ways, and setting the results aside for later. That kind of effort points to real planning and to a community where color was important enough to be worth all that work.

From Engraving to Drawing

Blombos and other Middle Stone Age sites show an evolution in how people made marks:

- Engraved patterns carved into ochre pieces and bone.

- Abstract designs (like cross-hatching) repeated across different materials.

- Finally, the drawn ochre "hashtag" on stone, indicating a new technique and fine motor control, much like writing.

The fact that similar designs appeared in both engravings and drawings hints at a stable, shared symbol system. People were using multiple techniques, from scratching to grinding to painting, to produce the same sign across mediums.

Putting the Evidence Together

When we line up Indonesia, Spain, and South Africa, the neat story of a sudden “creative explosion” in Ice Age Europe does not hold up. What we see instead is a long, slow, global story of different groups learning to push thoughts out of their heads and onto stone, bone, and cave walls.

How the Dates Line Up

| Site (Location) | Species | Art Type | Dating Method | Age (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blombos Cave, South Africa | Homo sapiens | Abstract cross-hatch drawing on stone | Stratigraphy + OSL | ~73,000 years BP[5] |

| Maltravieso, Spain | H. neanderthalensis | Hand stencil | U-Th (calcite crust) | >66,700 years BP[3] |

| Ardales, Spain | H. neanderthalensis | Red-painted stalagmites | U-Th (calcite crust) | >65,500 years BP[3] |

| La Pasiega, Spain | H. neanderthalensis | Red scalariform (ladder) symbol | U-Th (calcite crust) | >64,800 years BP[3] |

| Leang Karampuang, Indonesia | Homo sapiens | Narrative hunting scene with therianthropes | Laser-ablation U-Th | >51,200 years BP[1] |

| Leang Tedongnge, Indonesia | Homo sapiens | Figurative warty pig painting | U-Th (calcite crust) | >45,500 years BP[9] |

| Chauvet Cave, France | Homo sapiens | Figurative animals and scenes | Radiocarbon | ~30,000 years BP[10] |

Why Art?

Why did different human groups, separated by thousands of miles and species, all begin to mark their world with red ochre and carved lines? Archaeologists and cognitive scientists point to several overlapping reasons:

- Group identity and social bonding: As populations grew, symbols may have helped mark who belonged to which group. Shared designs and styles functioned like team colors, creating a sense of "us" that scaled beyond small kin groups.

- External memory: Narrative panels like the scene in Leang Karampuang act like an external hard drive for cultural knowledge. They store information about animals, hunting strategies, and stories in a form that can outlive any one storyteller.

- Aesthetic and emotional expression: The urge to decorate, to pattern, to leave a handprint, appears deeply wired. Art transforms raw rock into something charged with memory and meaning.

Maybe the most striking point is this: when both Neanderthals and early modern humans are doing these things, it looks less like a rare talent in one branch and more like shared wiring. Give our brains time, pigment, and a surface to work on, and they seem to look for ways to leave marks behind.

Conclusion

So what do we learn when we follow the dates, the pigments, and the lab reports all the way down the list? The Sulawesi hunting scene at more than 51,000 years ago, the Neanderthal paintings in Spain over 64,000 years old, and the 73,000-year-old drawing from Blombos Cave all point in the same direction: art is not recent, not a European invention, and not something reserved for us, Homo sapiens.

Instead, creativity looks like a family trait. Whether it was a Neanderthal blowing pigment over a hand in a Spanish cave or a modern human sketching a cross-hatch on a stone in South Africa, the underlying move was the same: take a mental image and push it out into the world so it could be seen by everyone.

These marks were not idle doodles. They took planning, materials, cooperation, and a shared belief that the image mattered enough to keep. Read together, they feel like records passed down through our shared family tree: we imagined, we marked, we remembered.

If there is a single thread running through all of this, it is simple and oddly comforting. Long before there were museums, styles, or art critics, there were people saying as art, “We were here. This mattered.” When you make a sketch, design a logo, or trace your own hand with a child, you are not starting something new. You are stepping into a very old conversation, adding one more print to the wall.

References & Further Reading

- Oktaviana, A.A. et al. (2024). Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago. Nature.

- PubMed abstract — Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago.

- Hoffmann, D.L. et al. (2018). U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art. Science.

- University of Southampton — Earliest cave paintings were made by Neanderthals.

- Natural History Museum — The oldest drawing ever found is a stone "hashtag".

- National Geographic — 73,000-year-old doodle may be world's oldest drawing.

- Henshilwood, C.S. et al. (2011). A 100,000-year-old ochre-processing workshop at Blombos Cave. Science.

- The Guardian — Oldest known picture story is a 51,000-year-old Indonesian cave painting.

- National Geographic — 45,500-year-old pig painting is the world's oldest animal art.

- Chauvet Cave — overview and dating.

- Leakey Foundation — Found in a cave in Indonesia: world’s oldest figurative art is 51,200 years old.

- Big Think — Overview of the newly dated 51,200-year-old Leang Karampuang panel and the global record of cave paintings.

- Anthropology.net — Earliest known cave art reveals a 51,000-year-old hunting scene in South Sulawesi.

- Newsweek — Cave art 51,000 years ago is oldest evidence of picture stories.

- PMC — Open-access paper detailing the Leang Karampuang laser-ablation U-Th dates and narrative scene.

- Artnet — World’s oldest cave art: Indonesian pig and therianthrope scene dated to 51,200 years.

- Google Arts & Culture — Indonesia’s 51,200-year-old narrative cave art in Leang Karampuang.

- Google Blog — Oldest known evidence of storytelling through art, featuring the Leang Karampuang mural.

- Clarkson, C. et al. (2017). Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago. Nature.

- Smithsonian NMNH — Homo heidelbergensis species overview.

This article includes the following interactive elements: click-to-expand images, inline Wikipedia links for key terms that open in a new window, citation hover popups, and external-link previews.

Like to discuss or comment on this article? See my page on Facebook.